What the Americans call moonshine, the Irish call poteen

And the Scottish call hand sanitizer

(Jimmy Carr, 8 Out Of 10 Cats Does Countdown, 2017)

© Alec Dalglish, 2018

About 13% of English words are not spelt the way they sound

And that percentage increases to 100 in Glasgow

(Jimmy Carr, 8 Out Of 10 Cats Does Countdown, 2017)

So now it's done. All the new MSPs have been sworn in and the Scottish Parliament is open for business again. You remember I had two big hopes for this Parliament. First, that the SNP would get an outright majority on the constituencies, so they could tell the Greenish Inquisition tae git tae fuck, and they missed it, though I guess there is little they could have done. Second, that the Alba Party would make enough of an impression to get one MSP in each region, and that one was quite wildly off the mark, wasn't it? And of course, I really wanted Joan McAlpine holding her seat, and that was a big miss too. I'm in absolutely no mood to blame anyone or sling mud to the four winds, unlike some SNP zealots who tweeted some truly despicable stuff and showed everyone what a sore winner looks like. As Bob Dylan once wrote, "what's lost is lost, we can't regain what went down in the flood", so let's just move on. But first let's move back a bit and see how the well the last batch of polls before Election Day did, or not, and how it compares with the actual result. Here there are some odd similarities with the last poll before the 2016 election. Back then and again this year, they overestimated the SNP on the constituency vote, and by almost the same amount. And, again like in 2016, this year's polls underestimated the SNP and the Conservatives on the list vote, and overestimated the Greens. Troubling.

So the end result was also off by a couple of seats, just as it had been in 2016. Interestingly, if you feed the actual results into an uniform swing predictor, it will deliver 63 SNP seats, 60 constituencies and 3 list seats. Just saying that uniform swing can be quite crap too. Interestingly, uniform swing would have given the SNP Dumbarton, which they missed. But wouldn't have given them Edinburgh Central, Ayr and East Lothian, which they gained. Now it's interesting to check which pollster was the closest to the actual results. Panelbase's last poll, published a week before the election, definitely wins on the constituency vote as they had the SNP on 48% and 27% ahead of the Conservatives. That same poll also wins on the list vote, as they had the SNP on 39% and 17% ahead of the Conservatives. Panelbase was also one of only two pollsters who got the Green list vote right on 8%, Opinium being the other one, and were also closer with the Conservative and LibDem list votes, on 23% and 6% respectively. So I guess it's a tie between Panelbase and Opinium here, rather than an outright win for Panelbase. YouGov, who were the best in 2016, definitely fucked it up this year, wildly overestimating the SNP constituency vote and the Green list vote. And the worst by far this year was Savanta Comres, missing the SNP vote by 6% on both the constituencies and the lists in their last poll for The Scotsman, that predicted the SNP down to 59 seats overall. Ouch. I think it's fair to say that the identity of the client introduced a bias here that goes well beyond the usual sampling variations or house effects. But I can't even challenge them on this as they blocked me on Twitter for no reason but questioning their compliance with British Polling Council disclosure rules. Weird election indeed, where one of the pollsters turns out to be the sorest loser.

Some constituencies did not fit any pre-determined pattern. Once such case is Rutherglen, which appeared as a weak SNP hold with Labour breathing down their neck, but saw the SNP increasing their majority. The only explanation that works is a combination of Unionist tactical voting and a shift of "soft Yes" voters from Labour to the SNP. In Rutherglen, the latter vastly outnumbered the former and proved there was no Margaret Ferrier Factor punishing the SNP, no matter how often BBC One Scotland brought it up. Then the SNP had a close shave with a total trainwreck in Banffshire and Buchan Coast, just as I hinted in my last pre-election article. Losing 10% of the vote and prevailing by only 772 votes looks awful in what was once Alex Salmond's seat, where the SNP bagged a majority of the popular vote at all previous Holyrood elections. But, as I said last week, the SNP would definitely have asked for it if they had lost the seat. We also have the Greenies arguing they had been "robbed" list seats by some obscure far-right group, without offering any solid evidence. As always twisting the basic math of AMS, and hoping their sequacious cultists will swallow it. Sore winners turning into sore whiners is just what we need right now, innit?

Nicola Sturgeon is the hardest politician

You wouldn’t want to get into a ring with Nicola Sturgeon

(John Pienaar, Have I Got News For You?, 2021)

© Alec Dalglish, 2020

There are five million CCTV cameras in Britain today

That’s one for every person in Scotland

(Jon Richardson, Ultimate Worrier, 2018)

There are many lessons to be learned from this election. First one is how quick the metropolitan enlightened English press, that is The Guardian, were to help the SNP in their savaging of the Alba Party and personal smear against Alex Salmond. The main reason for this being of course that they support the same kind of social liberal policies, most prominently with their unquestioning promotion of identity politics, which have replaced Independence at the top of the SNP's manifesto for now. There is no doubt that the Unionist parties and media quickly realised that the Alba Party was more of a threat to them than to the SNP, and behaving as the SNP's little helpers was the surest way to nip it in the bud. The enemy of my enemy is my friend and they all lived happily ever after. The Unionist parties also used the full potential of anti-SNP tactical voting. This is made quite painfully obvious by the long list of seats they held against all odds (Dumbarton, Edinburgh Southern, West Aberdeenshire, Dumfriesshire), thusly depriving the SNP of an outright majority on the constituencies, which was always the one recipe for the truly unquestionable victory they needed, instead of the quasi-status quo we had. The chart below also shows how much tactical voting there was even in seats that appeared out of the reach of the SNP even on very good day (Eastwood, North East Fife, Edinburgh Western). The results there obviously do not reflect the true strength of the winning party in such constituencies, but show that the Unionists have mastered "better safe than sorry" much better than the SNP.

Here I included all seats held by Unionists before the election on one side, then only those they held at this election on the other side, as tactical voting was quite obviously more prominent in these. As the Liberal Democrats held all of their four constituencies, I set aside the two mainland seats, as Orkney and Shetland have a life of their own, where general patterns found elsewhere don't apply. Interestingly there was also pro-Independence tactical voting in Edinburgh Central, the key marginal that a Green vanity candidacy handed to the Conservatives on a sliver platter in 2016. There the SNP benefited from a combination of the Green vote going down, and a fair share of Labour voters switching to the SNP. Other Green vanity candidacies in other seats did not significantly impact the SNP's results. In some cases like Glasgow Pollok, the SNP's vote share fell slightly, but Labour voters switching to the SNP almost compensated for votes lost to the Greens. In the most controversial case, Galloway and West Dumfries, the Green vote proved irrelevant in the end, after fears it might cost the SNP a possible gain. The SNP would have missed it anyway due to the extraordinary amount of Unionist tactical voting. There were also some hints of Unionist tactical voting for the Tories on the regional lists. But it's far less convincing as we know a fair share of Labour constituency voters switched to the Greens on the lists, so the numbers actually don't make the case one way or the other. I can't think of any credible situation where tactical list voting clearly gained the Tories a seat from the SNP or the Greens. The only example I have is actually one where it backfired, with Labour losing a seat to the Conservatives in Highlands and Islands, and only due to the high proportion of LibDem voters who switched to the Tories on the list.

In Edinburgh, they have salt and sauce

In Glasgow, we have salt and vinegar because we’re classy

(Susan Calman, QI: Revolutions, 2020)

© Alec Dalglish, 2015

Instead of scuppering the Scottish nationalists

A Scottish Parliament has made them more popular

Now, that might only be a blip but, with her own politics, her own news,

Today’s Scotland feels a lot more than 400 miles away from Westminster

(Andrew Marr, History Of Modern Britain, 2007)

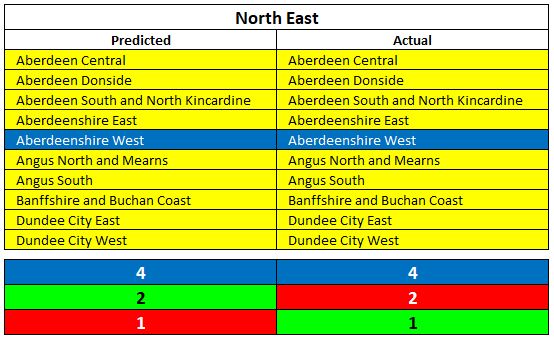

Now the final test is how my last projection compares with the actual results, on a seat by seat basis across all regions. It's also an opportunity to assess how my model fared, in comparison to the more widely used method of uniform national swing. Uniform national swing on both votes, based on the same batch of the last five polls, would have delivered 65 SNP seats, just like my model. But these would have all been constituencies, with no list seats on top, while my model was a wee smitch closer to the actual result with 64 constituencies and 1 list seat. Relying on the regional crosstabs of the polls avoided me two misses in West Aberdeenshire and Dumbarton, which uniform swing allocated to the SNP. But uniform swing allocated Dumfriesshire to the Conservatives, while I had it switching to the SNP. And both missed the Labour hold in Edinburgh Southern, as tactical voting is obviously something you can't readily incorporate in any projection model, as it would require some seat-by-seat tweaking of the projection, which defies the fundamentally statistical foundation of the model itself.

Overall I have scored 2 misses and 71 hits on the constituencies, a 97% hit rate. I will certainly not fault either my model or the polls for that, as I have already explained in some detail why I missed Dumfriesshire and Edinburgh Southern, and I'm quite sure everybody would have. Then I have 7 misses and 49 hits on the list seats, a 88% hit rate. This is based solely of the number of seats, and not the order in which they were allocated, which is pretty much irrelevant, given the number of factors at play here. I will not fault my model here, as the formula to allocate seats under the Scottish variant of d'Hondt is straightforward and basic maths. There is no way you can get that one wrong, unless you are politically motivated to make it look more complicated than it is and misrepresent it. The misses here are generally the result of polling errors, as polls regularly underestimated the Conservatives and overestimated the Greens on the lists. Polls also underestimating the SNP's list vote is far less of a factor here, as they were bound to not bag any list seats in six regions anyway. Missing a third of the list seats in South Scotland, my worst result, is also a ripple effect of missing one of the constituencies there. So I consider my overall result of 9 misses and 120 hits, or a 93% hit rate, quite satisfactory. After all, some people have won the fucking plaque on Four In A Bed with lower scores than that, haven't they?

Now that I'm done patting myself on the back, there is one last and important message from this election's results. When you have all the results in, even a 10-yr old can figure out the average and the standard deviation of every party's vote share, can't they? Or call Rachel Riley to the rescue, she might need a wee fee to cover all her legal bills. The standard deviation doesn't say much by itself, as a higher average vote share will almost automatically generate a high standard deviation. But the ratio of standard deviation / average does matter. The lower it is, the more evenly spread your vote is across all constituencies. Here the SNP is a clear winner with a ratio of 0.17, compared with 0.51 for Labour, 0.54 for the Conservatives and 1.49 for the Liberal Democrats. This might sound fine at face value, but it begins with a blessing and it ends with a curse. Because that's the textbook situation where a party with this sort of results is relatively immune to small swings, but can be fatally hurt by larger swings. Of course any swing against the SNP would have to be huge to make them lose the next election, but we've seen this before, haven't we? Labour, 2015, 24% swing. Never say never again. Just saying.

There’s nothing noble about being on the side that loses

You find the biggest kid in the playground and you stand next to him

(Werewolf Milo, Being Human: The War Child, 2012)

© Alec Dalglish, Daniel Gillespie, 2010

I know a thing or two about prophecies, they’re bullshit and mind games

Seems to me that they only get dangerous when you actually start believing in them

(Annie Sawyer, Being Human: The Graveyard Shift, 2012)

Now the last page in this chapter was the Airdrie and Shotts by-election, for Neil Gray's former Commons seat. The actual results shows that both my hunch and my calculations were way off on this one. And this is one of a few cases where I still don't know if I'm fully gutted or just slightly miffed to have been proved wrong. My last projection was a close call, with Labour gaining back the seat by 1% on a high level of tactical voting from the Conservatives and LibDems. But also based on the 6 May results, when Labour polled 12% higher than their national average in the overlapping Holyrood constituency, and the SNP only 3% higher. So the combination of all factors made a Labour gain quite likely. This was also supported by expectations of a very low turnout, which statistically hurts the SNP more than the Unionist parties. Then everything went a different way to what earlier trends and recent Commons polling in Scotland indicated. Turnout fell from 40k to 22k but the SNP slightly increased their vote share. The impact of tactical voting was a 6.9% swing to Labour, twice that at the Holyrood election a week earlier, but still massively below what would have unseated the SNP. Then the most extraordinary thing here is that the SNP were able to keep their troops mobilised for the by-election, after what was undoubtedly a strenuous Holyrood campaign. Guess they also heard the warnings about Labour withdrawing resources from Hartlepool when they realised it was already lost, and throwing the Full Monty and his python at Airdrie and Shotts. The message got through that nothing should ever be taken for granted, and it worked.

Despite this convincingly brilliant victory in Airdrie and Shotts, the SNP can't escape the simple fact that Labour still have quite a voter base all over the Auld Strathclyde area, even before tactical voting is factored in. On 6 May, Labour overperformed by 9% in Central Scotland and Glasgow, and by 6% in West Scotland on the constituencies. Which I think is a quite fair assessment of their strength in these regions, as tactical voting went in totally different directions depending on the constituency, and looking at the bigger picture across the whole region irons out the differences. And, even after losing part of their votes to the Greens, they still overperformed by 6% in Central and Glasgow, and 4% in West on the lists. The only other region were they overperformed on both votes was Lothian, and by smaller margins. There are in fact enough regional variations all over Scotland to make the case that uniform national swing is probably no longer the safest way to predict the results of future elections. I also believe that some patterns seen at this Holyrood election could easily be duplicated at a Commons election, despite the different nature of the two votes. Unionist tactical voting is just one of them. You also have to account for the ancestral Scottish tribalism and ferality, which are probably more of a factor on the Yes side, if recent events are any indication. As usual, only time will tell. Or some unforeseen by-election.

Now eagerly waiting for the first poll about the 2026 election, just to check the level of buyer's remorse from SNP voters who switched to the Greens on the list, instead of Alba.

No constitutional chopper has come down between Scotland and England

But it feels as if a slow, gentle separation is taking place

Like two pieces of pizza pulled apart, still connected

But only by strings of molten cheese

(Andrew Marr, History Of Modern Britain, 2007)

© Alec Dalglish, Craig Espie, 2012

No comments:

Post a Comment